03 The Doctor Returns

“The Doctor returned last night”. Harriet fluffed her mother’s pillow, carefully pulled back one corner of the duvet cover, and then helped her mother up from her wheelchair onto her bed. The transfer was an effort for both women, so it was a moment before their conversation continued.

Mother spoke next, ”I’m so glad he got back safely. I don’t know why he goes on those dangerous voyages when his daughter is still a child.”

”He’s the Anderson’s top scientist. I imagine he has to do what he’s told.”

He didn’t have to leave his daughter in the care of that brute he has for a brother-in-law.

“Jimmy is a brute, but Katherine takes good care of Caitlin.”

“Dutiful wife and sister.” Harriet spoke with contempt.

Thus far the conversation was to type: Harriet and her mother’s opinions about Doctor Hofstaedter and his family had not changed for years.

”What did the Doctor say when he saw Daniel in that awful cell; or was he too tired to notice? You know how tired people can be so good at not noticing.”

“He was plenty tired when he arrived. He looked terrible, like he hadn’t slept in months. But he noticed Daniel, alright.”

The conversation paused for a minute while Harriet’s elderly mother propped herself up, so that she was more comfortable. When she was done, Mother eagerly asked, “What happened?”

Harriet replied, ”The moment the Doctor saw Daniel in his cell he just stopped. His whole entourage stopped, the porters, his man, Caitlin.”

”His daughter was there?”

“Of course she was there. She hasn’t seen her father in well over a year! You couldn’t separate them.”

“She’s a sweetheart, isn’t she?”

” I sometimes fear that her heart is too good for this world.”

”She’s going to have to lose some innocence; the world’s certainly not going to get more virtuous on her account.

“She already has. Remember how she looked when her Uncle took the money she was going to use to bribe the auditor.”

Mom nodded in agreement then asked, “So what did the Doctor do?”

“For a long moment he didn’t move. I didn’t even see him breathe. It was like he was trying to find the energy to do anything at all. But when he moved again, he moved quickly. First he whispered something to his man, who disappeared up the stairs with the porters in tow. Then he told his daughter to go to bed. After that he turned around and marched out the door.”

“What did Caitlin do?

”She followed her father, of course. She’s like her father very determined once she’s chosen a path.”

“It took almost an hour for the Doctor to return but I didn’t notice the time because the foyer was filling up with people. Every time someone new arrived I had to tell them the story all over again.”

“What about Mrs. Ellison?”

“She was standing on the edge of the foyer. Bruno was with her, of course.”

Mother nodded as she pictured the scene in her head. After a sip of water, Harriet resumed her story.The Doctor returned with his daughter and a blacksmith. By this time his eyes were dark red and his hands were so unsteady that Caitlin had to open the door for him.

“Had he been drinking?”

“The Doctor never drinks!”

“Habits change, daughter. Tell me more about Mrs. Ellison.”

“Be patient, Mother. I’ll tell you about Mrs. Ellison when it matters.”

Harriet straightened her skirt, and then continued, “The Doctor walked straight to the cell, past Bruno, Mrs. Ellison, everyone, as if we didn’t exist.”

”Harriet, I’ve known Doctor Hofstaedter since he was a child. Be certain he knew everyone’s location and rank.”

Harriet ignored her mother’s comment and continued. She said, “The Doctor stopped one step before the cell. He turned to face Bruno, his hand on the hilt of his saber, ready to draw. The locksmith and Caitlin were behind his back. The locksmith fired up a gas torch. He could have picked the lock, but the Doctor had ordered him to break the gate into pieces.”

Mother laughed and clapped. “What wonderful news! Why that’s the best news.” She quickly became serious. ”Harriet, if your father had lived, this whole episode with Daniel would never have happened. You know that.”

Harriet nodded her head obligingly. She didn’t know that, but liked to share her mother’s dreams about what might have been.

Mother asked, ”What happened to Daniel?”

When the gate to his cell was destroyed Daniel immediately ran out and cowered behind the Doctor. Bruno tried to intervene, but when the Doctor drew his sword , he thought better of it and backed off toward the door.”

“What about Mrs. Ellison?”

“She was screaming that Daniel’s imprisonment was legal, that he was a hoarder, and that his imprisonment was a mercy because he should have been hanged for what he did.”

“Such a fight, in such a small space.”

“It was like a stage at a theatre. Everyone but the main actors had run up to the mezzanine or out into the street to watch from a safe distance.”

”Did Bruno attack the Doctor?”

“Bruno was carrying a large wrench in his right hand – the one he uses with the boiler. You could see him trying to decide whether to attack the Doctor, and mark my words he was going to, when the door was pushed open by the Doctor’s man, who had arrived with two tough looking friends. I don’t trust that man, but I understand now why the Doctor retains his services.”

Mother nodded and Harriet continued speaking, ”The Doctor stepped toward the entrance to join his people. Caitlin and Daniel were one step behind. They formed a line at the door. The Doctor was in the center. His daughter was on his left side, in front of the stained glass window. The Doctor’s man and his ruffian friends were by the entrance to the mud room.”

“Where was Daniel?”

“While they were gathering at the door, Daniel slipped out and ran away. He didn’t even have shoes on.”

“What happened next?

“It was the Doctor’s show. Even though he was so weary he could barely stand”. He said in a public voice, ‘Why was Daniel imprisoned?’ It was like the beginning of an ancient Greek trial.”

“How do you know that?”

“Mother!”

“Alright, so tell me about Mrs. Ellison.”

“Mrs. Ellison was standing at the foot of the stairs under our License. She said, ‘Its like I’ve been saying, the prisoner is a hoarder. There’s a war on right now, and he had a sack of rice he wasn’t sharing. There was a fair trial and he was convicted. We should have executed him.'”

“What did the Doctor say to that?” Mother asked.

“He ignored Mrs. Ellison. Instead drew his sabre and pointed it at Bruno and asked in his most proper voice, ‘Who is this man?’ Bruno stepped into the middle of the foyer, two paces from the Doctor. He bowed and said, ‘Bruno Constantinus, at your service’.”

Bruno can be polite? Mother asked caustically.

”He brandished his wrench before he bowed”, her daughter replied.

“Didn’t the Doctor’s man do anything?

“He moved to block Bruno but the Doctor signaled for him to back off. But let me finish! After Bruno introduced himself, he walked right up to the Doctor and said very politely, Mister, you are upsetting the Lady.”

”Lady…!”, Mother laugh while she slapped her knee.

Harriet nodded, ”You’re of the same mind as the Doctor. He took two steps sideways – toward the entrance and away from his people – and shouted so loudly he could be heard across the street, ‘This man is calling Mrs. Ellison a Lady! Hah! There is nothing noble about that woman!'”

”The Doctor was making room for his sabre, wasn’t he?” Mother asked.

Harriet nodded. “Then Bruno did something very stupid.”

“The poignard? Mother hazarded, with a worried tone in her voice.

Harriet nodded, ”Bruno pulled back his cloak to reveal that rusty knife he calls an heirloom.”

Mother used her pillows to raise herself half way out of her bed, “Oh no. Bruno didn’t … ?”

“The instant Bruno placed a hand on the knife the Doctor killed him with one cut through the heart.”

“In front of Caitlin! Poor child. Is she alright?”

“I don’t think so know, but she can’t be. As Bruno collapsed she smiled that flat terse smile of hers.”

“Her secret smile. What about Mrs. Ellison?

“When Bruno died Mrs. Ellison went crazy. She started shouting at the Doctor, and pounding her fists against his chest. She went on about food shortages and how dangerous hoarders are, and how letting one person get away with crime encourages everyone to try.”

“What did the Doctor do?”

“He didn’t do anything, he just studied Mrs. Ellison, like she was a specimen.”

Mother laughed.

Harriet continued, “Guess what happened next? Two policemen showed up!”

Mother was so thrilled the story had another chapter she slapped her palsied knee again. Her daughter continued, “The Doctor was the person with the highest rank at the scene of the crime, so of course he explained to the officers why there was a corpse. The police accepted the Doctor’s claim that he had killed Bruno in self-defense. One policeman actually ticketed Bruno for possessing an illegal weapon. He said, ‘That’s what happens when commoners wear swords.'”

The policeman’s comment fired Mother up. She said, “That cop is an ass. Bruno was just too stupid for his weapon.”

Harriet smiled at her Mother but her narrative did not miss a beat, “You won’t believe what happened next. Two more policemen entered with Daniel, handcuffed, between them.

”What did Mrs. Ellison do? She she try to show them the court records?”

“She wanted to say something. She stood right behind the Doctor, muttering to herself like she was practicing her lines.”

“But she didn’t?”

”No. The Doctor didn’t give her a chance. He was very civil. He invited all four policemen to warm themselves by the coal heater, and sent his man upstairs for drinks. The newly arrived policemen said that they were here because they had found Daniel, without any shoes, at the carriage depot. Because he had been branded with this address, they suspected he was a felon or escaped slave.”

“As his man handed the policemen drinks, the Doctor informed them that Daniel had been a prisoner here but new evidence had come to light, and he was now free.” Harriet imitated the Doctor’s formal style of speech as she recounted his words. ”He gave the officers extravagant gratuities and asked them to please ensure Daniel got shoes, a change of clothes and a coach ticket to Anchorage. The Doctor asked for their names and ranks to ensure compliance. As the policemen left, the Doctor shouted after them in a loud, hearty voice, ‘Officers, I will commend you to the Anderson.'”

”That’s so like the Doctor”, Mother said drily.

Harriet continued, “As soon as the policemen were gone the Doctor shooed everyone out of the foyer promising that everything would be set in order at the next board meeting. He had his people take care of Bruno. They did a good job. There’s no sign of blood at all.”

”That’s quite a story, Harriet. Did it really happen or is that pitiful man still imprisoned under the stairs?”

”Daniel’s free Mother. He’s at his parent’s house in Anchorage.”

Mother reached over to clasp her daughter’s hands in hers. ”Harriet, I fear that my generation has let you down: we’re leaving you a world far worse than the one we inherited. Just like our parents and grandparents did.”

”Nonsense Mother. The Doctor is back. All it takes is a few good people to turn everything around.”

”Harriet, there are never enough good people.”

01 Mr. Market

Our boat, the Yéil, a seven mast, 250 foot schooner, skirted around the ruins of the US Bank Tower and sailed into Los Angeles Bay. The Bay is a narrow but long stretch of water between Long Beach Island to the west and what is left of southern California to the east. We were traveling to a village of perhaps 5,000 souls, where the natives lived – if the hyperbolic words of our scouts could be trusted – amidst a treasure of ruins. Our progress through the Bay was slow because we continuously had to stop to take soundings. The Captain cursed the fools who had made his inaccurate charts, but to me his anger seemed self-indulgent. The collapse of Los Angeles into the Pacific Ocean is a work in progress: better to curse the Earth for moving.

As we neared our destination, we were greeted by a ramshackle flotilla of rafts made of tires and scavenged pieces of plastic. The thin metal masts on these contraptions were fashioned into crude S shapes that looked like dollar signs. We dropped anchor in a sheltered lagoon perhaps three hundred metres from the edge of the village, which was situated in the deepest part of the bowl formed by the bay. The tire-rafts were too light- weight relative to the wind, tide and the waves to maintain a fixed position, so instead bobbed in a slow rotation around us.

The Yéil was oriented to the south-west. Long Beach Island was directly in front of us. The island at most points was little more than a sandbar. On its northern tip, which I now faced, it was far more substantial because a web of ruined expressways had trapped enough sand and seaweed to sustain agriculture. The natives grew several types of fruit including mangoes, pineapples and oranges. The crops had to be genetically modified because the combination of intense summer temperatures, salt-saturated winds and contamination from ruins made the environment inhospitable to most flora: only tough plants grew naturally, particularly bay hops, scrubby pine trees and sawgrass. Our estimate of the island’s total population – 20,000 – was far higher than seemed sustainable.

A dinghy, which I was surprised to see powered by a 2 horse power engine, pushed through the rafts and pulled up along side us. It had two inhabitants, a fair-skinned, lanky young man with knotted blond hair, and a much darker skinned woman with henna-red hair and freckles. The man was shirtless, save for a strip of cloth he tied neatly around his neck, and draped down his chest. He wore finely woven blue pants, which were held up by red, white and blue striped suspenders. The woman was partially covered by a ragged dress, which was also made of red, white and blue material. Her hair was tied into neat braids to which were fastened small coins; she had currency tattoos all over her body.

We threw a rope ladder over the side of the boat. I gestured for the man and woman to come aboard. They declined. Rhonda, our staff anthropologist, mimed that we were interested in visiting the village. The natives did not immediately reply. Instead, the man turned off his boat’s engine, rose, placed his thumbs into his suspenders – no mean feat in a dinghy – and addressed us. He spoke in unaccented Television English. “I see that you are from Alaska.” He nodded toward the image of the raven painted onto the bow of our ship. “You’ve come a long way. Catch.” He threw each of us a fruit. Rhonda caught her orange, I caught my lemon on a rebound, and the Captain – a bluff, unsteady man – had to retrieve his avocado from a pile of rope. The native spokesman frowned pensively as he sat down. Before he had a chance to interpret the dropped avocado as some form of bad omen, our anthropologist said, “My name is Rhonda. May we stay here for a few days? We would like to purchase – or trade for – provisions. We have many things that will interest you.”

Again the native spokesman stood up. As he did so his small boat was buffeted by the wake made by our nearly stationary, but large ship. He managed to remain balanced. “Nice to meet you Rhonda. My name is Cody. I am the PIMCO.” He spoke his title in a loud, strong voice that carried far out into the bay. He then gestured toward his female companion.

“This is Luck.”

After we returned their greetings, Cody resumed speaking, “You are welcome to stay until the anniversary of Default Tuesday, which you must know is in two days. We have fresh water, and plenty of avocados, tomatoes and citrus fruit.” A small wave knocked his boat; he hastily sat down.

At the request of Doctor Hofstaedter, the aloof, aristocratic man who represented our Patrons’ interests on this expedition, Rhonda and I made first contact. We were assigned this dangerous task ostensibly because scientists are better at establishing trust than soldiers.

Our transportation, a motorized rubber boat called a Zodiac, was lowered into the water by a hoist. Rhonda and I descended separately using a rope ladder. The Pacific Ocean was choppy enough that entering the boat was awkward, but we were unencumbered so did so with no incident.

If the wind had been favourable we would have rigged a sail, but it was not. We turned on the engine and headed across the lagoon toward a spit of land on the north-east side of the native village. The flotilla of tires haphazardly followed us. About 200 metres inland from the spit I could see the ruins of an office building poking out of the ground. According to my charts, it had once been twenty stories high; now ten of those stories were buried. A symmetrical, relatively intact, second tower was beside it, to the south. Although the intact tower was also skewed and buried, to my amazement, its electric lights still worked.

Our craft was faster than any of the native ones, including Cody’s dinghy so we had to cut our engines to avoid beaching before our hosts. We landed just behind Luck and Cody, beside a highway on-ramp the natives used as a dock. The ruined north tower was directly in front of us. To our left, perhaps 100 metres down the beach, was a large collection of lean-tos built in the lee of the partially intact south tower. This was the island’s main population center.

Rather than mooring our Zodiac, which ran the risk of occupying someone’s parking space, we dragged it a short distance onto a desolate section of beach. The natives made no effort to assist us, but when we were done Cody gestured for us to follow him toward a large fire pit situated at the edge of the village.

The natives were dressed in scavenged beach-ware. Most men wore shiny shorts, no shirt, and sandals made of automobile tires. Their hair was roughly cut, when cut at all, and almost always tied back with electrical cables. Some cables still had plugs attached. The women for the most part wore only bikini bottoms, although some wore smocks made of re-purposed materials; a few wore nothing at all. All of the natives were lean; none looked malnourished. In fact, I was struck by how healthy they were. Even the most wealthy Alaskan has some form of blemish – perhaps a chipped tooth, pock mark or callous. With the notable exception of tattoos and ritual marks, I could not see even one blemish or scar on any of the hundreds of natives who gathered around us.

Rhonda, noticing this as well, whispered to me, “They’re all genetically engineered.”

I nodded. It was a plausible hypothesis. Although there are few genetically modified people in the Republic of Alaska, there are many in California and the Oregon Territories.

Cody gestured for us to sit on a piece of driftwood, which we did. Luck sat to our right, on a large, padded office chair. She made a point of being oblivious to our presence. Rhonda began to speak, but Cody gestured for her to be quiet. We sat cross-legged, resting the palms of our hands on our knees.

After several slow minutes Cody leaned over to me and whispered, “San Bernardino County is beside your right shoulder. That is very unlucky. You should face it directly.” He indicated that I should shift my torso 45 degrees clockwise, so that I was facing due east.

The setting sun shone so brightly the Sierra Nevada mountains looked like burning gold. In the foreground, the tips of sky-scrapers poked out of the water like lesser mountains. They too looked like they were burning, but with the kind of fire created by sparks of light. On the beach, directly in front of me, the natives had constructed a sculpture out of rubble and rebar that echoed the shape of the sinking metropolis.

As the sun set several natives appeared with firewood and kindling. A woman stepped out of the crowd. She carried a small, carved box in which lay a metal canister with a spout. After making a ritual gesture, she removed the canister and poured fuel onto the kindling. Her attendant used a square silver lighter from a sequined pouch to light a fire.

Rhonda choose this moment to attempt to speak again. She addressed Cody, but pitched her voice so that those nearby could hear, “We have a gift for you.” As Rhonda said this she removed a zippered purse from her satchel, which she opened and displayed to our hosts. The purse was stuffed with hyperinflation dollars. She deposited them in the sand half-way between Luck and Cody.

Luck picked up the gift. She carefully closed and re-opened the zipper on the purse, as if zippers had powerful juju. She then handed the purse to Cody, who opened it and removed a wad of ancient currency “They are all singles”, he cooed. Our scouts had told us that the natives valued US one dollar bills because the Hyperinflation had made them rare. When Cody had finished examining the gift he passed it to Luck, who gave it to an attendant.

We waited for a response. If Cody or Luck gave us a gift in return, that would indicate a sense of equality between us. If they didn’t, they thought of our gift as tribute, and us as inferiors.

They gave us nothing. Instead, Luck leaned forward so that her face was only a couple of centimetres away from Cody. She spoke so that everyone nearby could hear, “It is time to play the market. Let us find out whose side they are on, yours or mine.” As if her words weren’t sinister enough, when she spoke the crowd rearranged itself into two distinct camps, one behind Cody, the other behind Luck. Cody’s people wore medallions shaped like dollar signs around their throats, while Luck’s team was adorned with currency tattoos and coins.

“I’m on it”, Cody replied with gravitas. He removed a handful of red and green dice from a plastic pouch that was lying in the sand near his feet. With a small, sharp gesture that engaged only his left forearm, he threw them onto the beach. He dropped onto his knees, leaned forward, and used his right forefinger to trace a line in the sand that connected the dice. The line pointed upward to the right.

While I waited for Cody’s verdict, I looked at Rhonda to see if she thought we should make a run for it. She avoided my gaze, which was an answer to my question: she was staying. I was poised to flee.

Cody spoke, “Mr. Market is happy today.”

Luck stormed away without a word.

Rhonda struck up a conversation with Cody. I could not hear what they were saying, but thought it best not to intrude. I scanned the village for Luck. I spotted her in the middle of a crowd of large, young men who were sorting through a heap of metal on the eastern edge of the village. Periodically one of them would examine a piece of rebar, checking its weight and balance, as if choosing a weapon. Beyond Luck’s group – toward the dock – three women with long grey hair hovered over a cooking pot. They looked like they were brewing a potion. The witches were but a few metres from our Zodiacs – there were now two. The boats were guarded by a pair of Alaskan marines.

It was now dark, and I need light to explore, so I saw no reason to stay. I signaled my intention to return to the Yéil. Rhonda acknowledged me with a wave of a hand – she was preoccupied by her conversation with Cody.

I departed in one of the Zodiacs. Both marines stayed behind. When I reached the Yéil I went straight to bed. I fell asleep in an instant.

The only people awake when I arose early the next morning – aside from the watch – were two divers whose job it was to assess the salvage potential of the sunken metropolis. I checked in on Rhonda; she had not returned.

I was anxious to get an early start because I knew my scope of activity would be sharply curtailed the moment the economic assessment was done. Whether any part of this site would be protected from our miners depended on what I could discover during the next few hours.

Although I was in a rush, I used sail power to get to shore because the wind was with me. I landed just south of where I had done so yesterday, perhaps 100 metres closer to the village. With the exception of a border collie and a lone woman practicing yoga, the beach was empty. The dog, surprisingly healthy looking considering the local living conditions, decided that I was the most interesting thing happening this morning, so chose to accompany me. I wondered if the mutt’s genes had been engineered.

My goal was to investigate the mostly intact south tower. I intended to approach it indirectly, via the ruined north tower, because I did not want to be seen entering it.

I walked north-east along the beach toward the land spit that abutted into the bay. At the point where the spit intersected my path I encountered a group of native fishermen who were preparing for a dive. Their gear, snorkels, flippers and diving suits, was mostly made of old, brittle plastic. One man wore a rusty metal tank on his back that once contained compressed oxygen but was now empty. The fishermen casually greeted me in well-spoken English, but were preoccupied with their work, so otherwise ignored me.

On the other side of the spit I discovered a long hill, or more accurately a kelp-covered wave of asphalt, that originated in the ruined north tower, cut across the beach and went out into the bay. The hill was porous. When the light from the sun was right I could see collapsed bits of highway, half-buried under the silt and kelp.

I carefully climbed up the asphalt wave. I followed its crest for a dozen steps – toward the ruined tower – and then slid into a ravine, unobserved – except for the dog, who still followed me. The ravine was also part of an abandoned highway. I followed it straight to the north tower.

The tower was beyond ruined: all of its windows had long since broken, creating a glittering beach of glass and concrete dust at its base. All that was left was a 10 metre skeleton of rebar and steel beams.

When I passed through some form of security gate, perhaps 20 metres away from the building, a line of green arrows embedded in the roadway became illuminated. The arrows led directly to a large, rectangular metal door at the base of the tower. When I reached the door, I saw that it guarded an entrance. Although the part of the building above the ground was ruined, the below ground portion had been somewhat repaired after the Hayward Quake. The door could not be opened from the outside. However, there was a small service door beside it. I entered the building the way people must have 200 years ago, by pressing a green button. This triggered a buzzing sound, and caused the service door to open inward. Because of a difference in air pressure between the inside and outside, a current of air urged me inward. I entered. My dog companion did not follow.

The space was illuminated by green parking signs, most of which still worked. I was on an asphalt road at the top of a small hill, which I quickly walked down. When I reached the bottom of the hill the road curved to the right and entered one of the odder examples of repurposing I have ever encountered: a parking lot created out of an auditorium, on the eleventh floor of a buried building. The parking lot itself was small – there were spaces for 20 cars, half of which were filled. The cars were all parked on what had once been the auditorium’s wooden stage, although one row of parking had been cut into the clam-shell seating that formed a semi-circle around the stage.

At the edge of the orchestra pit, which was at the base of the stage, I saw a red exit sign, which hung over a pair of wide doors . When I reached the exit, I saw that it opened onto a tunnel to my ultimate destination, the south tower.

The walls of the tunnel were lined with pale blue ceramic tiling and were lit by full-spectrum automatic lights, which suggested late Digital Age technology. On the walls of the tunnel there were safety instructions stenciled in a radiant paint that you could only view from certain angles. That paint was possibly the most advanced technology I’ve ever seen.

The tunnel ended at a circular glass door. When I passed through it into south tower, the entire atrium lit up. It was like the building itself was greeting me.

Although the atrium was intact – no windows were broken, a tile mosaic on the north wall was flawless, and the marble floor was brightly polished – it was an odd sort of intact because everything was slightly skewed: the main structure of the building – indeed the entire landscape – tilted north-west. Rows of offices lined the wall to my right. There was a bank of elevators in the center, and a large entrance to my left through which I could see hovels.

I approached the elevators, and pressed the up button. Despite my boundless curiosity about every aspect of this amazing building I did not hesitate about my destination, which was the top floor. The rich and powerful like to be higher than every one else, so this building’s treasures were likely concentrated there. I watched mesmerized as a flashing display above the elevator bank counted down from 21. When the number hit 11 a bell chimed; the door in front of me opened and I entered. I pressed 21 on the control panel; the doors closed. I expected to be whisked away. The ride was so smooth it took me a moment to realize that I was moving at all.

The elevator doors opened onto what had once been a reception area. Illumination once again accompanied my entrance. To my right I saw a desk, behind which was a hand painted sign that said “City of New Los Angeles”. The sign was propped up by the skeletons of two office chairs. On the wall behind the sign I could see the faded letters P, M and O.

I walked past the guard desk, through a pair of unbroken glass doors, into the inner offices. I scattered a small fortune in metal cans, as I did so.

The space before me had once been divided into cubes by cloth-bound moveable walls. The cloth on these walls had long since rotted away, revealing yellowed plastic frames. Many cubes still had desks, chairs and office machines. That none of this had been scavenged made me suspect the natives considered this a special, possibly sacred space.

Behind the cubes, along the wall immediately in front of me, was a line of offices. The walls and doors of these offices were decorated in ornamental plastic to make them look wooden. My attention was drawn to a large corner office to my left. It stood out because of the votive candles at its base and the $ symbol that had been etched into its plastic maple-wood door.

I tried to open the door, but it was locked.

I had a portable acetylene torch with me, which I used to destroy the lock. When I entered the office, the burnt handle fell off into my hands.

The office was undecorated except for a desk against the left hand wall, and a bank of filing cabinets on the right. The filing cabinets were locked, but the desk was not. I opened a drawer. It was full of paper documents. I picked up the one on top. It was an excerpt from a hand-written diary, which I read,

After the helicopters left we forced our way into the north tower. It was empty, except for one computer engineer. He was having trouble backing up his system, and had unwittingly missed the last chopper. Although I tried to stop it, he was killed. I know nothing about him except that with his death another bit of knowledge is gone.

The chime of an elevator bell startled me

I crawled out of the office, and hide behind a nearby row of dividers. There was a security mirror on the ceiling above me, which allowed me to view most of what happened next.

I watched Cody’s reflection as he exited the elevator and walked over to the office I had just explored. He was dressed simply, in tire sandals and shiny blue shorts. A large $ medallion hung from his neck. I lost sight of him as he entered the office itself, but I could hear him open drawers and shuffle papers. After a moment he exited the office, and walked resolutely toward the elevators. There was a chime, and the sound of an elevator door opening, then closing.

The moment elevator door closed I rushed to the office, swept every loose piece of paper into my satchel, and ran towards the fire exit on the north-east corner of the building. I descended to the eleventh floor, where I was pleased to discover an exit into the courtyard between the north and south towers.

Because this was likely my last chance to explore unhindered, I decided to return to the Yéil via a round-about route that took me initially north and west – away from both the native village and my ship.

At the western edge of the courtyard I discovered a path that wended toward the northern tip of the island. From a distance, the path seemed like it was a smoothly paved relic from the Digital Age, but on closer inspection I saw that it was a more recent construction made of salvaged pieces of concrete and asphalt. In the distance I could see the ruin of the US Bank Tower, hovering over the northern tip of the island.

After I had walked north for perhaps one kilometre I stumbled upon the entrance to an untended garden. It was surrounded by a fence made of long, grey pieces of wood. Where the fence intersected the path there was a gate on which hung the sign, “City of New Los Angeles Sustainable Garden and Waterworks.” I entered through the space between a gatepost and the fence.

As I walked through the orchard, along a path that followed a slight upward incline, I realized that the garden was tended, but by machines, not humans: there were signs of automated controls everywhere, including monitoring devices, and a still functioning irrigation system.

Thirty minutes of slow walking later the garden gave way to an open area, in the center of which was a huge, flat building with long, narrow windows. There was a functioning engine on the western side of the building, which was attached to a pump. Beyond the pump was a semi-circular channel that sloped at an angle into the Pacific Ocean. The building – a desalination plant – was powered by a large, flat field of solar collectors which wrapped around its northern and eastern edges.

I walked around the perimeter of the building. From a distance it appeared intact. Up close I saw that it had been repeatedly vandalized. The vandalism reminded me of another great archeological site I had learned about in school: the ruins of Persepolis. The Persian capital city, reputedly the most beautiful in the ancient world, was destroyed by Alexander the Great. I remember asking a teacher why Alexander had done so and got an uncertain answer to my question: perhaps he was drunk, perhaps his soldiers needed to be paid with loot, perhaps he simply wanted to demonstrate his power.

The midday sun was burning my skin, so I decided to sit in the scented shade of a hedge row of blooming hibiscus bushes. My mind became quiet; for once in my life I forgot about violence and decay. I sat for I do not know how long listening to the sound of birds and wind, and the flow of water through sluices. The machinery itself was silent. Silent machines. That’s what you’d expect in Eden.

I removed my purloined documents from my satchel. The first folder that I opened contained correspondence between the Illinois National Bank and a woman named Miriam Livingston. The cover letter read,

I am pleased that our September wheat call options were in the money. I am writing to make arrangements for the delivery of the wheat to our warehouse at City Pier 3, 222 Ocean Drive, New Los Angeles.

I have enclosed a map, including the latest soundings from Los Angeles Bay. Needless to say, the geography of the region has altered dramatically in the past year.

Please excuse my use of snail-mail, but as you probably know the entire west coast telecommunication system is still down.

Regards,

Miriam Livingston

Chief Financial Officer, City of New Los Angeles

Attached to the letter was a reply from an organization called Abacus Legal Services. The logo at the top of the letter depicted a blindfolded woman taking a gold colored coin from a scale she held at eye level with her left hand. The address below the logo was Lakeshore Drive in Chicago.

I’m writing on behalf of Dean Wright at Illinois National. I’d like to begin by congratulating the City on its recent, very successful, hedges. Your wheat call options, in particular, were dramatically in the money.

As far as the delivery of the wheat is concerned, I am surprised a sophisticated investor such as yourself did not realize there was no delivery provision in this particular contract (please see Section XXIX of the master trade agreement).

I recommend you take your profits and purchase what you need on the open market. Most financial analysts anticipate that the price of wheat will continue appreciating for the foreseeable future, so act quickly.

We look forward to doing business with the City again.

Tim Russo

General Counsel

At the bottom of the letter, in embossed type, were the proud words, “Delivering the world to our clients”.

The next entry read,

I skimmed through the chronicle of Miriam’s attempts to avert the complete collapse of the City’s infrastructure. I read the last entry, which was written nearly two decades after the Quake,

I intend to kill myself with tranquilizers on the anniversary of the Hayward Quake.

I just re-read what I wrote: what terrible final words. I’m lucky and I know it. I lived most of my life at the peak of the Digital Age, and what a peak it was. I don’t know whether you surf, but if you do it was like catching the biggest wave.

Even now, its not all bad. We’ve created a Garden of Eden in our Sustainable Garden. I’m looking at it now. The idea was to expand it until it was the size of the earth, but we figured out how to make one too late. No. We got around to making our Eden too late. We knew what needed to be done last century. Some people think we’ve always known.

But back to my garden. That’s where I’m going to kill myself and why not? Its my reminder that despite our hubris we can still find glory.

I don’t know whether you’re reading God, but this time we almost rivaled you. Better watch your back – if we don’t become extinct first, next time we may go all the way.

We should have gone all the way this time.

Instead we collapsed one step before the finish line.

There were several more sentences that had been written, edited and crossed out.

I heard someone approach. I folded myself into the bushes, hoping that my khaki clothes would camouflage me.

The visitor was a marine from the Yéil. She entered from the east, through a gate that once was used by trucks servicing the desalination plant. Behind the entrance I could see the shell of an on-ramp to Highway 110.

The marine withdrew a map from her satchel. She rotated the map several times, apparently trying to align it with what she saw before her. When she had done so, she scanned the compound, pausing periodically to refer back to points on the map, as if taking inventory. When her scan was completed to her satisfaction she folded the map, and returned it to her satchel.

I stood up and took two steps forward. When the marine heard me, she quickly turned, gun in hand. She caught herself when she recognized me. “Good afternoon, Doctor”, she said. She was a stocky, dark-haired Corporal named Karana.

“Good afternoon”, I replied.

I thought it best to question what she was doing before she did the same to me. “Where did you come from? Have you been exploring?”

“What are you doing here?” she replied brusquely.

I said, “Doctor Hofstaedter suggested I find the source of the natives’ fresh water. I’ve found it, so I’m done here. I’m going back to the ship”.

“Good. I’ll walk with you. Let’s go straight to the east coast. I’d rather avoid the village.”

The desalination plant was situated at the crest of a small ridge, so our path took us through a field that sloped down toward Los Angeles Bay. The field – sparsely covered by sedge and flowering herbs – was no longer part of the island’s irrigation system although, judging from the broken control mechanisms we encountered, it once had been. After perhaps two hundred metres the slope flattened; we found ourselves walking through the ruins of a long, flat commercial mall. When we reached the coast the ruins gave way to an automatically maintained orchard. The border of the orchard was demarcated by a row of bougainvillaea, and a bleached wooden fence. We entered through an arched trellis crowned with roses, and then walked south along an ancient stone path. The bay was immediately to our left.

After a few minutes the path opened up into a circular area that, judging from the rusted remains of a see-saw and monkey-bars, must once have been a children’s playground. We paused to inspect a waist-high stone edifice.

“These used to be everywhere”, I remarked.

“What do you mean?” Karana replied.

“Water fountains.” I pressed a metal lever near the crown of the device and a 10 centimetre spray of water emerged. The water initially startled Karana. Once she composed herself, she stepped forward to try the device.

“Where do you pay?” she asked.

“The water is – was – free.”

“Even slaves drink here?”

“I don’t know about now, but there were no slaves when it was first made.”

“Huh.”

When I tell Alaskans about water fountains most find them fabulous. Perhaps Karana felt like she was in a fable, watching such a valuable resource be so casually dispensed, but if so she showed no signs. I wondered what she was thinking. Was she recalling one of the water usage lessons we all memorized in middle-school? Possibly her thoughts were personal. Was she was wishing that the Republic had free water she could afford to have two children?

I continued to speak, not so much to converse as to voice my thoughts. “Many historians think that free water might have been the key to American democracy.”

I didn’t expect Karana to respond, but she did. “Yeah. Could be. I could never explain America any other way. I mean back then people used to cross their Betters all the time, didn’t they? Totally chaotic. Maybe back then Patrons used water to keep their Clients in line. You know, like the Romans did with bread.”

I was still trying to formulate a response to this statement when Karana stiffened. She muttered something under her breath.

“What did you say?” I asked. I thought my voice was normally pitched, but it sounded loud in the suddenly quiet space.

Karana raised her voice, but continued to whisper, “There’s some men behind those trees. Maybe five.” She nodded toward the eastern edge of the playground. A second gang of six men now blocked the path to the south. I looked up just as a net enveloped me. Karana fired one errant shot before she too was taken down.

Someone sprayed me with a harsh substance that made my eyes and throat burn. I passed out.

I awoke in an office that had been turned into a prison cell. Karana was in the office-cell beside mine. I could see her through a slightly transparent plastic divider. We were both attached to metal beds by electrical cables wrapped around our ankles. Our mattresses were made from vinyl chair covers held together by thread made from carpet fiber. Our blankets, likewise, were made of crudely sewn patches of cloth. The area outside of our office-cells – the atrium of the south tower – was guarded by two large men with $ medallions around their necks, who were armed with sharpened pieces of rebar. The guards sat passively in half-rotted office chairs.

I called out to Karana; she did not answer.

Whoosh.

I looked toward the sound. Luck had just entered through the main doors, accompanied by an entourage of women. She passed by without acknowledging me, and went straight to where Karana lay. Her entourage followed.

Luck moved to the head of Karana’s bed. She carefully gathered Karana’s hair into a bowl of soapy water that one of her attendants was holding. The touch of water on her skin caused Karana to stir slightly. One of Luck’s entourage forced Karana’s mouth open, while another poured a milky liquid into it. Karana struggled feebly, but was too woozy; she eventually slumped back onto her bed, asleep. Luck finished washing Karana’s hair, and then spent the better part of an hour braiding it. She inserted coins into the braids, which made Karana glitter dully when she shook her head.

When Luck was done with Karana’s hair, she reverentially withdrew with her entourage. They whooshed as they exited the building.

I was still watching the entrance when a half-dozen tall, young men dressed in shiny blue shorts and dirty sneakers entered. They arranged themselves in a militaristic, though not quite military, formation in the middle of the atrium. Once in position, one of them whistled. A group of people were pushed through the rotating door into the office-cells opposite mine. The majority of the prisoners were old, although only a couple were obviously near death. The rest had injuries, such as missing limbs or digits. One baby – into whose mouth a cloth had been stuffed – had a hair lip.

Although most of the prisoners were either old or damaged, there were two exceptions: a teenage girl with scared green eyes, and a younger boy with scraggly blond hair and a subdued manner. The girl held the boy as if he were a teddy bear. I assumed they were siblings, perhaps orphans.

I fell asleep.

When I awoke Cody was standing beside me. He wore the same necktie and pants that he had been wearing earlier but he now also wore a dirty white jacket with thin black stripes. The jacket had a fringe made of dried human fingers. Cody took a seat near the head of my bed. With some difficulty, I sat up beside him, taking care not to touch his grisly fringe. One guard stood at the entrance to the cell, watching us with a blank, passive face. I noticed that his pupils were dilated.

Cody spoke, “Look at this.” To my surprise he withdrew an ancient communication device from a small plastic pouch hanging by a string from his waist. Like most Digital Age technology it looked functional rather than flashy. He proudly showed it to me. I thought he was offering it to me to look at, but he pulled it away as I moved to take it.

“Be careful with your price signals”, he said sharply.

“I thought you wanted me to take it. I’m very sorry.” I tried to sound contrite, but my parched throat could only croak. He signaled for some water, which I gratefully drank.

Cody spoke, “I was offering the Black Berry to you to look at. It will never be yours.” He handed the object to me again, in slow-motion. I accepted it with a show of reverence. The device was made of hard, dark plastic. When folded it fit into the palm of my hand; when unfolded it was the size of a small book. I turned it over. Its backside was a solar panel.

“Watch.” With a mischievous smile Cody leaned over me and pushed a button. To my amazement the Black Berry turned on.

The opening screen displayed the message, “Welcome Mr. el-Erian”. The message faded and was replaced by two runes: one with the caption email; and a second with the caption news.

Without thinking, I pressed the news rune. The screen immediately altered to look like a tiny, two column broadsheet, complete with photographic illustrations.

My heart nearly stopped: it appeared that the Black Berry was accessing the Internet. One of the challenges archeologists face while trying to investigate the technologies of the Digital Age is the interdependence of them all: typically one artifact can fully function only when many others are operational. With our limited resources and knowledge – and with so many things destroyed by natural disasters and war – we can only reconstruct parts of these networks. The Internet is the most extreme example of this. My expeditions have found thousands of personal computing devices, and each, a lonely monad, tells us so little because we are incapable of connecting them together.

The display on the Black Berry was divided into two columns. The column on the left-hand side was taken up by a small box with a right-pointing equilateral triangle in the middle. The right hand column contained a list of blue headlines. The date, which I could faintly see above the first headline, was from exactly two centuries ago: Default Tuesday. The infamy of the date mitigated my disappointment at discovering that this device was showing me a snap-shot of one day’s news, and was not connected to a network after all.

I touched the arrow. For the next 10 seconds there was an advertisement for a golf tournament. This was followed by a conversation between two men in suits, a taller, thinner one with blond hair, and a stockier man with darker hair that was parted in the middle. The two men were talking about how T-Bills had just been given a haircut. Although I recognized most of the words they spoke, many were used in ways that were mystifying to me. For example, the word “market” was used repeatedly, but in a broader sense than it is used today. For me, a market is a place where farmers sell produce. The men in this video used the word as if it were a substitute for all forms of economic activity, including mining, education and manufacturing. Phrases like, “The apocalyptic collapse of the bond market” suggested a religious aspect to the word.1

The specific meaning of the story was equally obscure. I deduced from the conversation that a T-Bill was some form of promissory note issued by the United States federal government, but I could not understand how a T-bill could have a haircut, nor why the blond commentator was so insistent that a 25% haircut was somehow insufficient and should have been “more along the lines of 50%”. It was as if he welcomed more of something that he thought was bad. He did so because of the “moral hazard” posed by small haircuts, which reinforced my feeling that there was a religious aspect to this story. I was excited: The Crash has always been attributed to political, economic and ecological factors. Religion is never mentioned. This was a big story.

The video faded to grey; the right-pointing arrow reappeared. I was silent, intently trying to understand the religious aspect of Default Tuesday and the Hayward Quake. The two commentators appeared to be proponents of two different sects, one which advocated stern practices and one which preached tolerance. It was possible that a religious schism contributed to the Collapse. Perhaps these two sects couldn’t agree on courses of action, even in the face of disaster, and as a result broken infrastructure was never repaired and the Digital Age ended.

Cody broke my revery, “Read a story to me.” he commanded.

“Certainly” I replied.

I moved my index figure over the list of blue headlines in the right-hand column of the main page.

- Was Malthus an optimist?

- Roubini predicts bull market

- Rebalancing your portfolio without Treasuries

- CFPB files suit against the Treasury

- Rogue seismologist predicts massive quake

- Fed Chief Shot

I clicked on the headline, CFPB files suit against the Treasury. The following story appeared,

“Excellent choice.” Cody said. “A very important text.”

I waited for Cody to say more. He gestured impatiently for me to continue.

I read,

“You can see how Regulators and Inflators are the enemies of Mr. Market”, Cody said gravely. I said nothing.

“Do you understand me?” Cody pressed.

I hesitatingly replied, “I don’t know. Its all about money. But I don’t understand half of what it means.”

I paused, wondering what I did understand. I said, “I am familiar with the assassination of the head of the Federal Reserve. It happened on Default Tuesday, just hours before the Hayward Quake.”

Cody leaned toward me so that his lips were near my ear. He said in a soft voice,“What do you know about the Ben’s death? That is one of our mysteries.” He paused, stood up, and then clapped his hands together, “Of course. You are the Ben!”

“No. You are mistaken …” I protested.

Cody grabbed the Black Berry. “Don’t try to regulate me!” he shouted with a staged furor. “You cannot tell Mr. Market what to do. One day he is up. The next day he is down. But every day he is chaos!” He exited the building with a whoosh.

Although Cody’s words suggested intense anger, his manner was ritualistic: I had unwittingly become an actor in this savage’s passion play.

I awoke to the sound of drums

Whoosh.

A dancer flew into the building. She, like all of the natives, was lean and tall. Her body was covered in henna tattoos of currency symbols; her lip was pierced with a $ shaped stud, and her dreadlocks were full of coins. She was followed into the atrium by a small rhythm orchestra, whose members were banging noisily on instruments made from found metal objects. The tattooed woman was dancing in an African style, alternately stamping her left and right foot. Her arms were bent; she shook her hands beside her head. Her right hand was missing a finger.

While the tattooed woman danced, the guards began to remove the prisoners. The baby went first. The cloth that had plugged his mouth when he had been brought in had been removed, but the infant was quiet. He was so still I assumed he was drugged or deathly ill. The children went next, followed by the adults, and the rhythm orchestra. The tattooed dancer went last.

Two guards came into our office-cells, a man who attended to me and a woman who attended to Karana. They cut our bonds with pieces of sharpened rebar, and then herded us through the revolving doors. My head was throbbing, and I was unsteady on my feet. I looked over to Karana. She was in far worse condition than I was. Her skin was tinged green; she had to be supported by her guard.

When we exited the building we found that we were on a stage, which was defined by a ring of torches. Luck and Cody were to our right, seated on office-chair thrones. They faced a large crowd. The prisoners were sitting on a long driftwood log between us and Luck. We were pushed onto the sand beside them. As I struggled to sit up, I saw that the full moon was watching us from the eastern sky.

Cody stood up. In his left hand he held the Black Berry, in his right he held a golf-club. He was wearing baggy surf pants made of shiny red material, a golf shirt, and the finger-fringed jacket I’d seen earlier. After a moment, the noise of the dancers, drummers and crowd faded into silence. He addressed the crowd with a loud voice, “Today is the 200th anniversary of Default Tuesday. Since that day we have been children lost in the wilderness, wondering what madness has Inverted the Yield Curve. Let us make the Sign of the Crash.” As he spoke, Cody drew a diagonal line with his left hand that started at his right shoulder and ended at his left thigh.

“Dow 14,000 Dow 100” the crowd chanted.

Cody replied, “Neither bonds nor equities” and then sat down. Luck stood up. She cleared her voice and said. “We will begin with the options.” As she spoke, the sibling prisoners were led forward by a female guard. The girl had a dazed expression on her face; the boy’s face was streaked with tears. The boy tightly squeezed the sister’s hand.

Luck said, “Is there a call for these orphan children? Because they are brother and sister they must be optioned together.”

A gaunt man with leathery skin and grey hair stepped into the torchlight in front of Luck, “I would like to buy a call option.”

“So would I.” A much younger man with dirty blond hair stepped forward.

The gaunt man looked aghast when the younger man spoke: he fell to his knees in the sand in front of Luck and said, pointing at the younger, fitter man, “Please cancel his bid. I am 41 years old and do not have a wife. This man has the rest of his life to breed. My time is running short. Please.” The second bidder watched the old man with a bemused look on his face.

Luck scowled as she said, “I deny your petition.” The older man began to protest, but thought better of it. He withdrew several metres, still prostrate, before he stood up.

Luck turned her back on the two bidders and addressed the crowd. “This is a zero sum trade. It must be cleared through arms.” As Luck spoke these words a man pulling a child’s wagon emerged from the crowd. He was wearing nothing but shiny blue athletic shorts; he had a collar around his neck that was connected to the handle of the wagon by a cord fashioned from carpet fibre. The rickety wagon, once painted fire-engine red, was now spotted by rust. Metal shards were piled on wagon; several toppled off as it was dragged through the sand. The wagon-puller went first to the older man, who chose a rusty metre-long piece of rebar for his weapon. The younger man chose a rust-free weapon that was short and thick.

The wagon man traced a fighting circle in the sand. When the circle was complete Luck shouted, “Begin.”

The older man concentrated on avoiding the swings of his larger, stronger foe, frequently moving to the edge of the fighting circle. When he stepped out of the circle he was roughly pushed back into it by the crowd. He had no strategy but to avoid being hit, and appeared to be motivated by nothing more than fear. Eventually the younger man landed a solid blow onto the older man’s right calf. The blow broke the skin.

The older man left a trail of blood as he crawled through the sand. The younger man calmly stalked him, as if waiting for an aesthetically pleasing moment to end the fight.

Someone in the crowd flung a piece of chipped concrete at the younger man. It struck him in the cheek but didn’t injure him. The blow nevertheless proved fatal: the distraction provided an opening the older man seized. He painfully, but quickly, raised himself part way up, and then with all of his force, he swung his weapon at the young man’s neck. The young man died the moment the blow landed.

The victor, his face crazed with pain, hobbled over to where his prize, the girl, and her brother sat. He used his weapon as a cane so was hunched over, like a crippled dwarf. He grabbed the girl by her right wrist and dragged her away into the crowd. The girl tried to hold on to the hand of her brother, but failed. The young boy tripped along after her, crying uncontrollably.

In the distance an engine back-fired.

Luck raised her arms beside her ears and waved her hands at the agitated crowd, while shouting, “Extras!” As she did so the drummers began to play with an insistent but irregular beat.

The prisoners were chided to their feet by the guards. One man, quivering with fear, did not rise until he had been struck several times by a sock stuffed with stones. The prisoners’ faces expressed emotions ranging from equanimity to terror.

The wagon man emerged from the crowd. This time his load was a large wicker basket that contained old plastic water bottles filled to the brim with a murky liquid. He dragged his wagon over to where the prisoners stood. A half dozen guards simultaneously approached the prisoners from behind. The crowd began to chant the mantra, “One day it is up, one days it is down, every day it is chaos” in time to the drums.

The wagon man approached the baby with the hair-lip first. A guard grabbed a bottle from the wagon, unsealed it, indelicately forced open the child’s mouth and poured liquid into it. The child sputtered and protested feebly. The guards moved down the line, offering drinks to each of the prisoners. Some hesitated before drinking; others simply closed their eyes and gulped. One man had to be forced to drink. The liquid was clearly bitter: several prisoners vomited and had to drink a second time. After drinking, each made the Sign of the Crash, and then took a seat on the driftwood log. They began to shake violently.

After ten minutes all of the prisoners had fallen over dead, save for one scrawny old man who – although he shook uncontrollably – had not received a fatal dose. Cody nodded to two guards, one of whom grabbed the old man’s hair and pinned him against his left knee. The second guard slit his throat with a knife fashioned out of a fractured copper pipe.

A crew of young boys collected the corpses and roughly dragged them to the beach. The corpses splashed as they were dumped into the Bay.

Luck shouted, “Bring the Regulator and the Inflator.”

Karana and I were hustled forward. Karana was so limp she had to be supported by two guards. Her shirt was flecked with vomit. I too felt nauseous but resisted offers of assistance. We were roughly pushed to the ground in front of Cody and Luck.

Luck handed Cody a leather pouch from which he removed a handful of red and green plastic dice. Cody threw the dice onto the ground in front of our prostrate bodies. He made a show of inspecting the dice. Still crouching, with a severe expression on his face, he traversed the perimeter of the torch-lit stage while waving his hands beside his ears. When he had completed his circuit he stood straight. He said in a loud voice, “Mr. Market is very angry.”

Luck spoke with a loud voice, “Begin with the Elizabeth.”

While Cody had been playing the market a metal gurney had been rolled – or more accurately, pushed – across the sand into the space in front of Luck. Two guards put Karana onto it. She was limp and sweating profusely. I was nauseous with fear; my saliva was so acidic I had begun to gag.

Cody raised both his Black Berry and his golf-club sceptre to the sky. He held the pose for a dramatic moment, and then handed his symbols of office to a retainer. In return he was given a tiny plastic box from which he removed a saw-toothed knife. He approached Karana.

I thought I heard a muffled cry from the direction of the dock. I could not be certain because the drummers began to play again. The tattooed dancer resumed her spirit-hands dance.

Cody ritualistic voice boomed, “Bear witness to what happens to those who would Regulate.” He placed Karana’s right hand in his. With one quick, sharp gesture he cut off her ring finger.

Karana’s screams were muffled by the t-shirt in her mouth. Then she was still. I assumed she had fainted and not died, but was by no means certain.

Cody solemnly picked up Karana’s bloody finger. He displayed it to the crowd like it was a trophy.

Luck shouted, “Rehypothecate the Ben!” In her right hand she brandished a stick of bleached drift-wood studded with nails, and decorated with strands of bright cloth. I stopped breathing.2

There was a loud crack. Luck collapsed. I heard another four cracks. The men who had been guarding Karana and me crumpled. A final gun shot grazed Cody’s shoulder and knocked him to the ground. The crowd dispersed in a chaotic stampede. It took several moments for my fear-wracked brain to register that a rescue party had finally arrived. I tried to stand up but was so disoriented and weak that I toppled to the ground. A marine rushed to my side. He threw his thick arm around me and began to drag me along the beach toward the dock.

“The Black Berry. The Black Berry.” My rescuer looked at me quizzically. Rhonda – who had accompanied the rescue party said, “He’s talking about the plastic device near that man’s right hand.” She pointed. “It’s incredibly valuable.” My rescuer, a Sergeant, hesitated: although Rhonda was not in his chain of command, she was the granddaughter of our Patron. Rhonda repeated her words as a command. Two marines fired at the ground in front of the scattering crowd while the Sergeant moved resolutely toward Cody.

When the Sergeant got to where Cody lay, he raised a pistol to shoot him a second time. Rhonda shouted with a tone of hysteria in her voice. “Don’t shoot! Bring him with you. We need prisoners.”

The soldier’s arm swerved, but he fired anyway. Cody twitched as a bullet punctured his right foot. The soldier picked up the Black Berry, carefully placed it into his satchel, and returned to my side. He signaled for the two Privates to pick up Cody’s limp body.

My vision was distorted; I had lost my sense of balance. Fortunately, my escort was strong enough to propel me forward despite myself. I made it all the way to the dock, where I tripped and fell face first onto the beach, immediately in front of where my rescue boat bobbed in the water. My marine escort swore colourfully while he tossed me into a Zodiac. I looked at Karana. She was vomiting over the edge of the other Zodiac.

The moment our boats pulled away from the beach a group of male villagers rushed to the dock. One native tried to get into a launch but was shot repeatedly; this caused the rest of the natives to pull back. The recoil from the guns rocked our boats.

Our Zodiacs curved around the on-ramp spit, and then sped into the bay. The desalination plant and gardens were now directly west of us, on our left. I heard a loud noise. I reached for a pair of binoculars that lay on a discarded pile of gear near my head. I raised them, with shaking hands, to my eyes. The desalination plant was on fire. It was surrounded by a crowd of natives. I began to curse violently. This made my rescuer quite angry. He shouted at me, “Shut the fuck up. We didn’t destroy the water factory. We just blew up some switches so those clowns can’t use it any more. We’ll loot it later.”

The air was full of popping sounds, which suddenly grew much louder. There was an explosion that I heard as a deep rumble and saw as a flash of light. The native surge around the desalination plant ebbed in the instant following the explosion, but the press of bodies was too great. The natives surged forward again. They began to pile on top of each other, desperately trying to get enough height to smother the now raging fire from above. Limned by the fire, and from a distance, they looked like a river of soldier ants flowing over dead prey, except they were far more disorganized than ants. The hapless souls didn’t even have buckets that worked.

As I watched clouds of smoke engulf the desalination plant, I wanted to shout at the marines, “It looks like we’ve forgotten how to blow up switches, doesn’t it? Big surprise. We’ve forgotten how to do all sorts of things. We can’t make photovoltaic cells, we can’t make integrated circuits, we can barely make elevators!” I wanted to say this but I had lost the strength to fume. Instead, I rested my tired head on a pile of cables so that I didn’t strain myself while I watched Eden burn.

Author Notes

The story begins when a ship called the Yéil arrives at Los Angeles, two centuries after California was destroyed (mostly flooded) as a result of the Hayward Quake. The name of the ship (Yéil ) is a reference to the trickster, Raven, who in Tlingit mythology is credited with (among other things) stealing the moon on behalf of mankind. Disruption is an important narrative device in all of the stories.

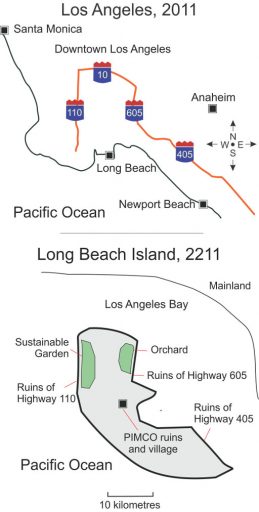

Long Beach Island was created when the Hayward Quake – and its numerous aftershocks – caused much of the western coast of North America to flood. The “Island” is what remains of the southern suburbs of Los Angeles. It is comprised of what is now the area west of highway 405 (the San Diego Expressway), including land currently under the Pacific Ocean. Its northern tip is the area between Highways 110 and 405, just south of downtown Los Angeles. Downtown Los Angeles is completely under water.

The set for the story is the shanty town that has grown up around the old Pacific Investment Management Company (PIMCO) headquarters, in Newport Beach. In the story, the ruins PIMCO headquarters is slightly closer to downtown Los Angeles than it is today.

I chose the PIMCO headquarters as the set for this story’s parody of financial shamanism because at the time of writing PIMCO had more bond assets under administration – $1.8 trillion in May 2012 – than any other company, and is the largest financial firm on the west coast of the USA. Mohamed el-Erian, the person whose personal communication device is featured in the story, is one of the two CEOs of the firm (along with Bill Gross).

The idea behind the parody is that when the Collapse happens, trade decays and, as a result, communities have to draw upon local resources in order to survive. The natives who live on Long Beach Island have few skills to help them survive – knowledge about bond and equity trading has become practically useless, and quite meaningless in a world without global financial markets. Over time this “knowledge”, because of its association with the lost wealth of the early 21st Century, gets turned into the magical language of the local religion. All this is to parody our current deification of free market economics.

The Sustainable Garden – aka Eden – was built during the Collapse. This is one of my favorite historical themes, that even in dark ages technology develops.

03 Chez Tulip

Although Tulip’s career as an entertainer may have fallen on tough times her bank account – judging from the opulence of her Mont-Royal nest – had not. She lived in a three story brick scamper-up that had it all, including stalking grounds, an aviary, and rat warren.

I was pleased to see that Tulip’s nest did not look like a crime scene at all. There was no bright yellow tape, no crowds of reporters. Since the forensics team left, there was barely a police presence at all – just one fierce looking Rottweiler, whose primary job was to keep news hounds and curious cats away.

The murder had occurred in the indoor stalking grounds, where Tulip – and her many guests – would hunt small animals for snacks and sport. A chalk mark outlined the position of Tulip’s body. She had died in a fetal position. In the midst of her oversize furniture the chalk outline looked small, like that of a kitten. This made me think of my own litter of pups back home in Willowdale.1

We both began to sniff.

I was investigating an area of floor unexpectedly rich in smells when I had the good fortune to discover a cleverly disguised trapdoor, which opened to reveal a cement box nest – the kind you found in every fashionable cat’s house during the 1970s. The floor of the nest was covered by a velvet pillow, on which there was an imprint of the ear of a dog.

In the middle of the pillow was a card with an inscription written in gold. It read, “Tulip, here is a symbol of how my entire pack will protect you.”

I sniffed. “Look here” I said, pointing my muzzle toward a tiny hair on the card. “A piece of a mouse’s tail.”

Mittens was beside me in an instant. He ignored the mouse tail, but sniffed the card thoroughly, and then said, “Barks, I smell a rat.”

Which was a point I fastidiously put in the Cat Detectives column. A bit of mouse at a crime scene was the antithesis of evidence. Mice always get to a crime scene first, and are almost never perps. Ratus ratus was another matter, entirely.

“Do you recognize this rat?” I asked.

Mittens never answered my question. At that moment a gust of wind triggered our next discovery – a card floated out of an open book onto the floor. Mittens carefully picked up the card by the edges. On it several sentences had been written by a bold cat’s paw. It was a copy of a letter Tulip had sent to her litter-mate and twin, Euphemia.

Mittens’ read in a slightly high-pitched, theatrical voice,

Dearest sister Euphemia,

Today I couldn’t stand one more second of Trouble’s damned feral inscrutability. I asked him what he was really thinking. He told me, in a flat voice – no affect at all, not even a purr – that he hates La Belle Dam but he can’t help himself. “Do you mean me?” I implored him. “You know what I mean” he said as he leaped out of the fire escape. I haven’t seen him since. I don’t know what I’d do without him. But I’m loosing him. I can tell from his scent, and unfocussed ears. I’m loosing him.

What can I do?

xx oo Tulip

Mittens’ concluded his oratory with a little bow.

“Are there other notes?” I asked.

“There are lots of notes down at the station. Tulip was quite a writer. But do you mean, was there anything incriminating? Non. Only this. Mais cela, c’est très intéressante, n’est-ce pas?”2

“It is interesting indeed”, I replied. “Let us inspect the book the note fell out of.” I hopped over to the small leather bound volume. It opened to a poem called La Belle Chat Sans Merci.3

I scanned the first few stanzas, and stopped at the fourth. In the left margin the words “Tulip” and “La Belle Chat” were written with a kittenish paw.

I flipped to the first page of the book where I found the following dedication, “To my cat-bitch twin sister on my birthday.

We have stereotypes about the love litter-mates and twins have for each other. Like many generalizations, the stereotype is both true and false simultaneously. I could see in the note Tulip had written Euphemia that the two sisters had a deep, abiding bond. They must have shared all of their experiences with each other. But it took scant effort to imagine that love erupting into a most vicious cat-fight.

I showed Mittens the book. He read the dedication and said, “We have another suspect.”

“Indeed”, I replied.

02 Who Does the Lioness Fear?

Our investigation began at the morgue, which was a nondescript block of glass and steel on rue Parthenais, four blocks west of the St. Lawrence River. We entered via a trap door on the east side of the building.

Mittens refused to inspect Tulip’s body in the presence of the coroner – who was a fastidious, copper-haired Spaniel named Sniffy – so we entered the small, grey operating theatre unescorted. We found the infamous feline beauty’s body laid out on a gurney. Although Tulip rested on metal, not marble, if you let imagination rule you, you could see her as a statue of Juliet in a final, tragic repose.

The first thing I noticed was her ears: they had been clipped to look like those of a lioness. Although I am a dog, or perhaps because I am one, my unthinking response to this was, “here lies a predator.” The effect created by Tulip’s wild ears was enhanced by the leopard spots tattooed onto her pearl white fur.

Mittens spoke to me with a plaintive voice, “Elle est très belle. Non, elle est trop belle”1 He groomed his whiskers with his bright, white polydactyl paws, and then continued. “If she were not so beautiful none of this would happened hien? There would be no story for the press, you wouldn’t be here, she would still be alive. We are driven to crazy, violent acts because of beauty. We are driven …”

I agreed with one aspect of what Mittens had just said. Although the case appeared complicated, it was likely that the murderer had a prosaic motive, like jealous rage. Nevertheless, I took issue with Mittens’ implication that motives only came from the instinctual side of the psyche. For me, Domestication is more than just a lid on the id. It has its own set of motivations, some of which can overpower our elemental drives. Perhaps Tulip’s murderer was compelled by lust or rage. Perhaps the murderer had a more subtle motive.

We began our investigation by sniffing the corpse. The dominant smell was a mixture of formaldehyde and disinfectant, but beneath that I found a more diverse layer of odours: feline, canine, and much to my surprise, pantherine. This latter mystery was solved by Mittens, who said, “She was wearing leopard-musk perfume when she died.” The Cat Detective shrugged, “It is all too much. C’est trop. Trop.”2

“Let us examine her wounds” I said, wanting to move our analysis along. Although I am not squeamish I don’t like autopsies because they are so raw: everything is stripped away by death – our hopes, our pretensions, our very spirit.

Tulip lay on her right side in a fetal position. Mittens lightly hopped onto the gurney and rolled her onto her back so that we could inspect the wounds on her stomach and neck. “Tabernacle” the cat said sub voce. Tulip’s fur was tufted by clotted blood; her stomach was lacerated in two places, and the interior of her throat had been exposed by one savage bite.

“Do you see these paw marks?” Mittens said, pointing first at the large cuts on her belly, and then at the mess around her throat.

“Dog” I replied without hesitation.

“Indeed. Can you recognize the breed?”

“Judging from the size, depth and angle I’d guess a large, muscular breed, perhaps a Shepherd or Rottweiler. I cannot tell from the scent, which is odd. You’d think there would be a molecule of smell in such a wound. There isn’t. All I smell is formaldehyde.”

“Do you notice anything odd about these paw marks, I mean aside from the fact they have no scent?”

I looked at the marks again. “Yes, I do notice something very odd. The wounds on the belly are from a left rear paw. I can’t tell about the throat.”

“A rear paw. Indeed! How do you know that?”

“From the shape of the wound. Dogs never move exactly forward, they always lead slightly from one side, which results in characteristic differences between paws. This mark is one that would be made by the back left paw of a right leading dog. I am one such dog myself.”

[I sat down and raised my paw for him to inspect; he saw how the my paws and claws had been slightly deformed by my orientation.]

“Could the paw that created these cuts have been not attached to an actual dog’s leg?” Mittens wondered.

I looked at Tulip’s wounds one more time. “Mittens, I think you’re right. These gashes move from bottom right to upper left – against the paw’s orientation. It would be impossibly awkward for a righting-leading dog to do this.”

“What can we learn from the wound on her neck?” Mittens hopped onto a small space beside Tulip’s right ear. From there he inspected her severed carotid artery. He sniffed then said, “This was an indelicate death.” His voice was more fastidious than sympathetic.

“Regardez!” Mittens lowered himself so that his nose almost touched the corpse. “There are fang marks on her neck. Tulip was bitten before her throat was slashed.” After a moment, he pulled his whiskers back, raised his head and said, “Cat”.

I took a corroborating sniff. “Mittens, can you identify the animal who did this?”, I asked.